Regaining Control of Unmanaged Dissociation

Dissociation is a beautiful, intelligent, and highly adaptive skill. It makes everything from the painfully mundane to the horrifically traumatic more survivable. It also gives us the gift of diluting physical pain, holding back overwhelming emotions, compartmentalizing daily stressors and difficult memories, and zooming out to gain different perspectives. When dissociation is unmanaged, however, its consequences can range anywhere from frustrating to life-limiting, scary, or even dangerous. Some of those experiences can include:

frequently losing minutes to hours of the day – possibly stuck in flashbacks, performing self-destructive or compulsive behaviors, zoned out, or doing other atypical actions,

unwanted switching between alters in a DID/OSDD system – possibly having no way to be filled in on what was missed later and/or switch back,

missing important events/meetings/moments due to not being oriented to the correct year, month, or day,

rapid-cycle switching between multiple parts of a DID/OSDD system (having no control over who is forward),

extended spells of non-responsive zoning out, becoming “locked in,” or even appearing ‘catatonic,’ for potentially hours,

unknowingly engaging in self-harmful or unlawful behaviors, without recollection or ability to regain control over the mind/body,

becoming so disoriented from the current time/place they’re unable to find their way home, to work, or another important location – potentially so unaware of the present year, they don’t know about GPS, smartphones to call for help, or who in their life today they should even call for help,

living life so detached - or “on autopilot” - for long enough that derealization leads to significant existential panic/paranoia (e.g. fears of truly not being real, alive, or having ever been in control of their body/life/etc, etc),

uncontrolled switches to child alters in public or behind the wheel, with no way to negotiate a switch back to a safe, more mature part,

having chronic, unexplained moments of not being present whilst driving, cooking, showering, out in public, or other very dangerous situations,

or many other disabling experiences.

For all these reasons and more, employing every last option to regain control over one’s symptoms may become a welcome solution. If learning about, and diligently using, your very best grounding tools isn’t enough, you’ve done journaling and internal communication with parts, tried modulation and containment skills for intrusive symptoms, and even asked for external supports to help keep you present, it may be time to turn to a higher-level intervention. Welcome in a 15-minute checksheet! You can download it here (to print or fill in on your devices).

What is a 15-minute checksheet?

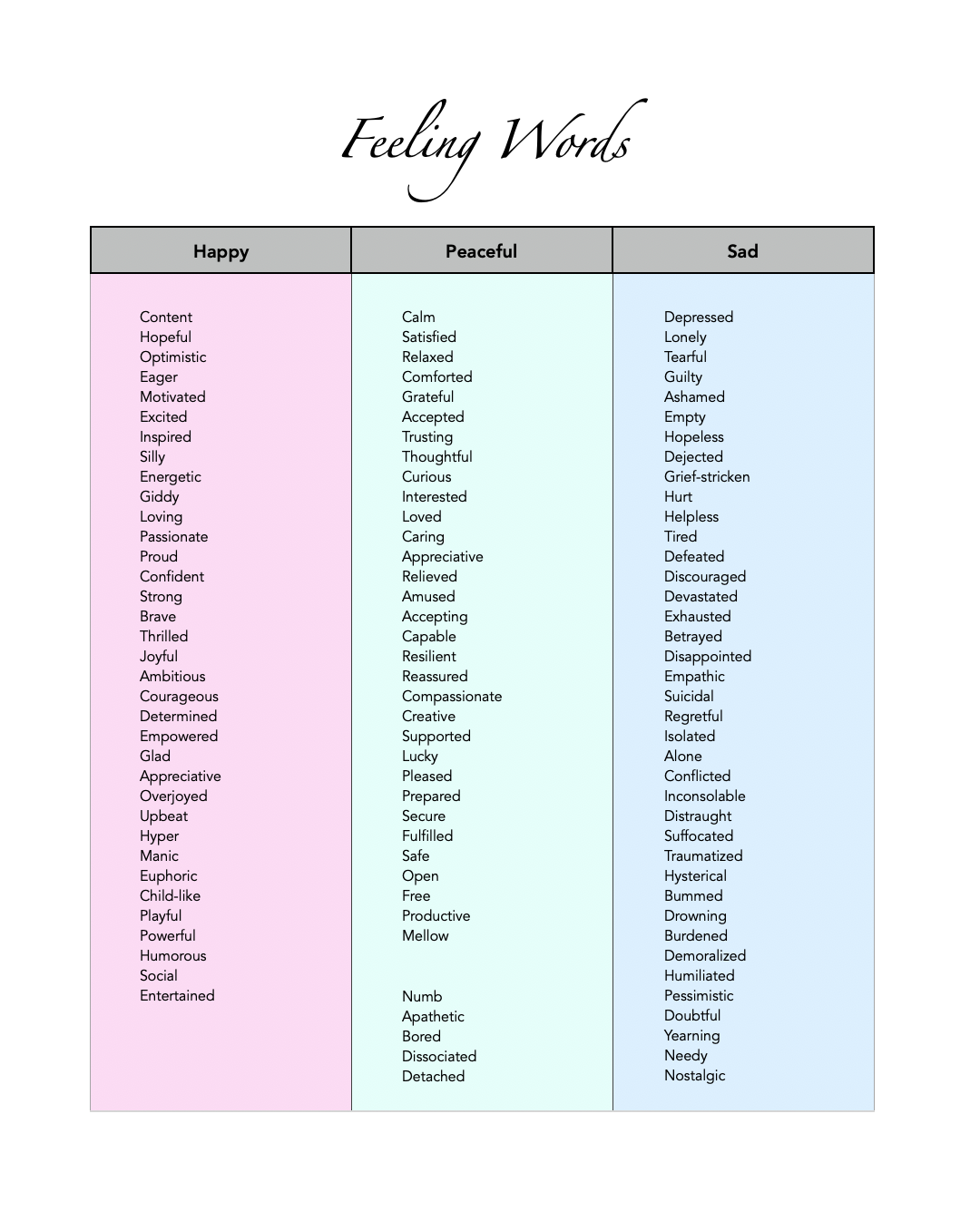

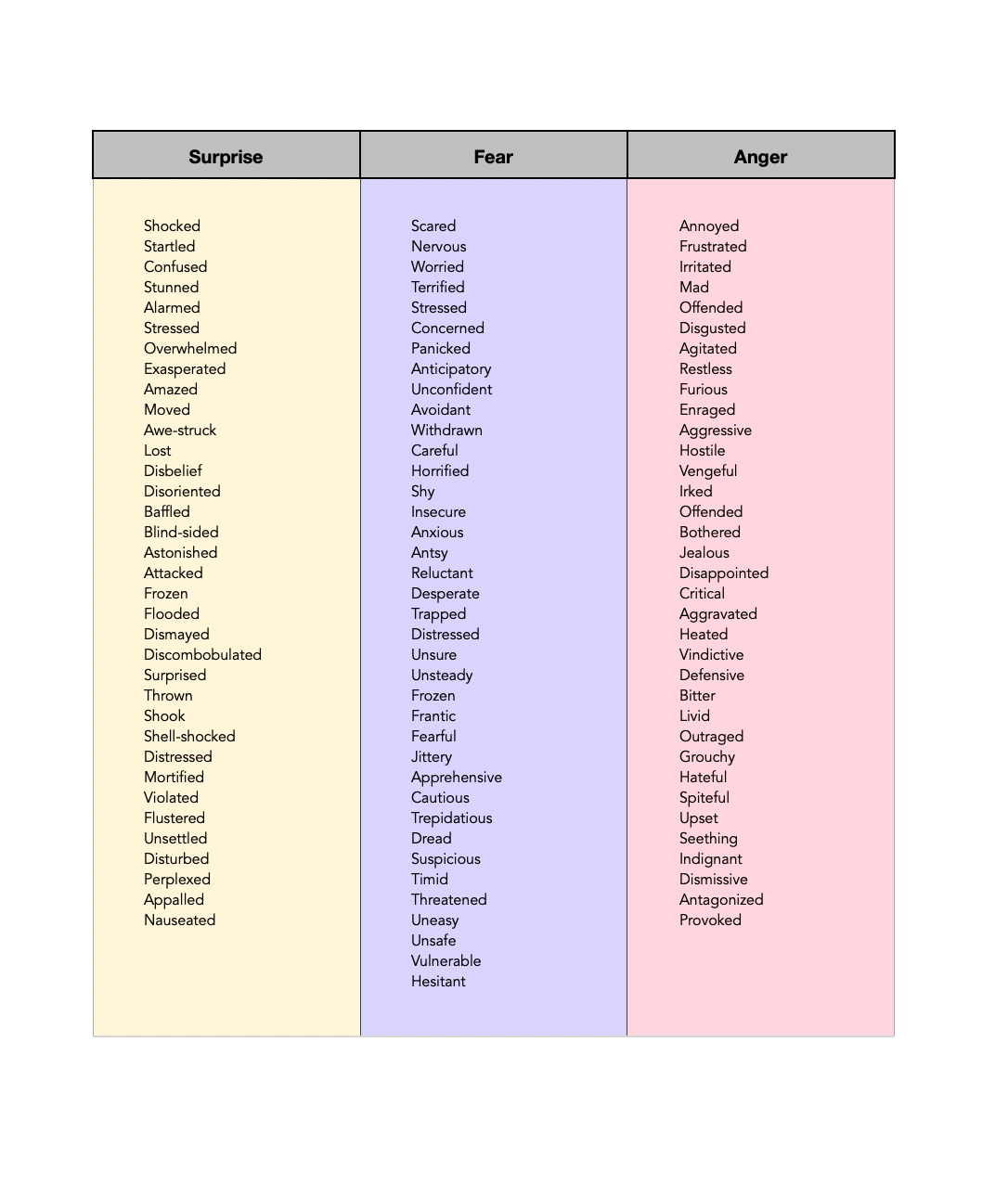

Conveniently, it’s exactly as it sounds! It’s a daily tracking sheet for folks to check-in every 15 minutes - jotting down just a few pieces of information like, where are ya, who are ya (DID/OSDD specifically), how grounded are you, what are you feeling, and what are you up to. While 15 minutes may sound incredibly intimidating, or even unreasonable, keeping track of things in this much detail can provide vital information that we just can’t get when unmanaged dissociation is stealing this much of our memory, sense of self-awareness, cognitive power, and our best problem-solving abilities.

This tool encourages us to pause, briefly connect with our internal experience, and jot it down somewhere for safe-keeping until we’re ready to look at it in the bigger picture. It takes the required brainpower out of it and helps us spot trends and patterns in the areas we’re getting hung up - ones we never could have noticed on our own. …at least, not when our dissociation’s this bad. Answering questions like:

Is there a certain activity I’m doing that keeps setting off this dissociation?

An emotion I’m feeling that’s prompting these huge gaps on the page every time?

Is there someone in my life who’s making me get extra spacey or begin rapidly switching?

An actual location or room in my house that’s fueling the fire?

Does it only happen at my job, at a certain relative’s house, or once I’m in my car?

Is it only in the mornings, right before bedtime, or some other oddly specific time?

Is my sheet completely blank from the time I make dinner onward? …why is that?

Do I only start seeing my grounding numbers tank after taking this one medication? Is it sedating me and/or do I need to talk to my doctor about it?

Do we have huge holes in the sheet right after one particular alter comes out? How can we work on that with them together?

…and so much more.

now comes the biggest question: EVERY 15 MINUTES, really?!

Yes, we really do want to encourage you to set a little alarm and at least try doing so for as long as you can stand it. As this is often an intervention for folks teetering on the edge of needing a Higher Level of Care (e.g. Intensive Outpatient, Partial Hospitalization, or Inpatient Care), the minute frequency is quite high. But, whether you utilize this tool in those 15-minute increments or spread it out to meet a less critical need, there is no shortage of valuable information to be gathered from a tool like this. Customization is key!

There are, however, some places folks can get a bit tripped up, so we wanted to include a section just for you! We also made sure to keep it with the downloadable PDF version (which also has a detailed List of Emotions, as that’s something many survivors of complex trauma can struggle with). This way you’ll always have it with you. No need to return or remember this page link! We know this is a tough time and you don’t need any added barriers.

Here are things that may help you along the way:

Blanks are okay - good even!

You aren’t expected to make every check-in time. If you could do that already, you wouldn’t be doing this sheet :) And, gaps give us information. That information will help us develop more effective solutions to combat your symptoms. Do your best to fill as many as you can, but consider a sheet with chunks missing a success!No back-filling.

It may be tempting to go back and fill in time slots you can reasonably recall. Try not to do this. Forgetting to jot things down still lets us know you weren’t 100% grounded or in a clear enough mind to remember to do the task (i.e. increase in ADHD symptoms, etc.). That’s more information for us! Unless you physically couldn’t write it down at the time (e.g. driving, doing a work task, making dinner, showering, etc), try not to backfill. If you do think it would be helpful to still have the other info, just notate somewhere (*) that these are retroactive answers. That will tell us a bit more about the quality of those assessments, in addition to your degree of present-ness at that time.Don’t panic, this task won’t last forever!

Just a handful of days is often enough to gather a lot of helpful information. If you can simply commit to giving your best effort those few days, you’ll do yourself a huge solid and be that much closer to getting your life back!Set yourself some timers if you need.

Nothing wrong with using all tools available to you to keep you on-task! Timers can also be easier than alarms since you can simply hit reset for a new 15-minute interval instead of having to create new clock times every quarter. If you’re getting startled or sensorily overwhelmed by all the timers, try a simple vibration alert instead.Call on parts inside to help!

Still struggling to remember? If you have parts inside, try assigning someone inside the job of watching the clock and reminding you when it’s time to check in. Parts like to feel important and valued; this can be a unifying experience and a good exercise in team building/bonding for systems.Too overwhelmed or wanting to give up?

If every 15 minutes really is just too much, try spacing it out to every half-hour. Or, conversely, start by checking in each hour, then tomorrow every 30 minutes, and the next day every 15. We’re just in search of helpful information, not aiming to flood, frustrate, or panic you. Some info is always better than none at all!Still too overwhelming?

Pick a chunk of hours in the day that you tend to lose the most time or struggle with other symptoms most prominently. Extend an hour in either direction and commit to just checking in as much as you can during that timeframe.Making it to every check-in?

Awesome! You’re doing so well with your grounding that you can now try spacing things out a good bit. Let’s see if things continue to hold without as much structure. If you start noticing more gaps without these consistent check-ins, we can re-evaluate and see if returning to 15 minutes would be beneficial. Or, you may discover that these are positive gaps due to living an active, grounded, well-lived life!

final thoughts

There is so much we can glean from such a meticulous tracking tool—even if your dissociation isn’t terribly unmanaged. Simply noticing and correctly labeling our emotions, observing patterns and catching where we’re spending too much of our time, discovering relationships or activities that may be harder on our health than we realized, becoming aware of or establishing communication with new parts inside, or even finding out that you’re more in control of your life than you realized — these all have tremendous benefits! And, you deserve to reap them. You deserve to live a life with full authority, agency, and confidence. May you reclaim exactly that if it’d been lost, or even better, unearth it for the very first time!

If, at any point throughout this exercise, you do discover yourself feeling particularly ungrounded, emotionally dysregulated, or more broadly overwhelmed, we encourage you to bookmark some of these pages for supportive symptom management: Grounding 101, Modulation 101, Color Breathing, and/or Self-Care 101. There, you’ll find hundreds (literally) of techniques to help you re-stabilize. Additional symptom management resources are listed at the bottom of this article!

We will be thinking of you and are here to answer any of your questions. As a reminder, you can download this fillable PDF to print or use on your devices. For therapists, you are welcome to offer this to your clients in either form. Healing tools should be for everyone.

MORE POSTS YOU MAY FIND HELPFUL:

✧ Grounding 101: 101 Grounding Techniques

✧ Flashbacks 101: 4 Tools to Cope with Flashbacks

✧ Self-Care 101: 101 Self-Care Tools

✧ Distraction 101: 101 Distraction Tools

✧ Nighttime 101 and Nighttime 201: Sleep Strategies for Complex PTSD

✧ Color Breathing 101: How to Calm Overwhelming Emotions and Physical Pain

✧ Imagery 101: Healing Pool and Healing Light

✧ Modulation 101: Using Dials to Modulate Intrusive Mental Health Symptoms

✧ DID Myths: Dispelling Common Misconceptions about Dissociative Identity Disorder

❖ Article Index ❖

FIND US ON SOCIAL MEDIA:

✦ Facebook: Beauty After Bruises // Therapy Box Project

✦ Instagram: Beauty After Bruises // Therapy Box Project

✦ Threads

✦ Twitter/X